Introducing: the Excalibur Fusion Fund

Now that we’ve got a tax exempt (501c3) non-profit organization it’s time to expand the scope.

As I have written and discussed often, I got sucked into the Farnsworth story almost entirely because of this riddle: How do you bottle a star?

Yes, I am endlessly fascinated by the origins of video and the decades of industrial intrigue and corporate avarice that have buried that remarkable story under the rug of revisionist history. Why, I’ve even written a book a book about it!.

But that book is really about the larger story of how Big New Ideas emerge on the fringe of orthodoxy – and the tribulations their emissaries experience, riding their ideas over the tumultuous tides of avaricious capital and through the labyrinthine gauntlet of vested interests.

From my experience, I have come to believe that video – one of the epic technological breakthroughs of the 20th century – emerged from ‘a well of knowledge’ that humans get only occasional access to – and that further down that same well lay the secrets civilization will require if it is even going beyond its fossil-fueled, 19th-and-20th-century industrial limits.

Hear me out:

Some of you will be familiar with the story of the moment Philo Farnsworth first conceived the Image Dissector – the electronic camera tube that made video possible. While just a teenager tilling fields in Idaho…

The notion of television never stopped tugging at Philo’s imagination. In his relentless pursuit of the subject, he learned about the properties of electrons. He learned how they could be deflected by magnets. He also learned how certain substances could be caused to glow when bombarded by electrons within something called a “cathode ray tube.” With those three elements—the electron, magnetic deflection, and the cathode ray tube—Philo began to believe he would find a solution.

Those elements crystallized in a instant when he looked back at the field he was plowing under the hot Idaho sun in the summer of 1921.

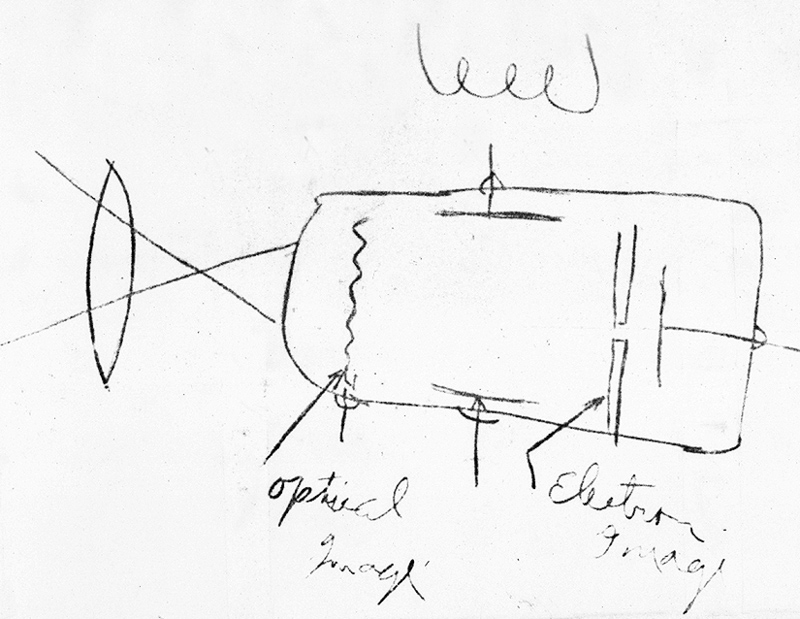

A few months later he drew this sketch or his high school science teacher in Rigby, Idaho:

…. and I contend that every one of the billions of video screens on the planet today (including the one you are looking at now) can trace its origins to that sketch.

In the years since writing the paragraph above, I have come to believe that there is much more to the story than just being observing those parallel furrows and being suddenly inspired to scan an image with similarly-parallel rows of electrons.

I think now that in the few years prior to that moment, the auto-didactic, aspiring young inventor assimilated a singular body of basic information that – with the added ingredient of his own divine intuition – made him uniquelly qualified to peer into what I am calling ‘the well of knowledge’ where he found not just the solution to ‘moving picture that could fly through the air’ but an even richer vein of extraordinary possibilities.

That conception in the Idaho field was just the first step on a journey of intuition-led learning that Farnsworth described as “a guided tour” along “the invisible frontier.” Over the course of five decades, that singular journey eventually led him to the cosmic riddles we ponder here at fusor.net.

A Fresh Perspective

Some of this fresh thinking about the mystical dimensions of the Farnsworth story flashed at me this past winter when I recorded the audiobook version of The Boy Who Invented Television.. As I read the material aloud for the first time in more than twenty years, parts of the narrative bore new meaning for me.

For example: There are a couple of passages at the end of Chapter 4 (The Damn Thing Works!) that illustrate Farnsworth’s unique modus operandi:

Phil had an uncanny ability to see a destination and guide his men there… “He could go through the orchard and just pick things out without breaking his rhythm,” one observer noted.

Cliff Gardner marveled that “The amazing thing about Phil was his ability to invent solutions without even realizing he was inventing. He was just providing solutions to the day-to-day obstacles we’d encounter. He always had an answer when one of us asked ‘what do we do now?”

As I read those passages I wondered anew: How did this farm-bred kid with little formal education know so much that he could earn more than 150 patents, singlehandedly refining electronic video to the point that it was first introduced to the public in the summer of 1934 – five years before David Sarnoff started re-writing the story at the New York World’s Fair in 1939?

.

And the answer I keep coming up with – silly as it sounds – is: Because… he… just… knew stuff.

And not just that he knew stuff, but that his unique path showed him more stuff: The weak signal form the first Image Dissectors demanded a novel approach to amplification, starting with the electron multiplier he built into the tubes’ anode stem. That experience led to the development of the muiltipactor tube, which in turn suggested his experiments with the spherical multipactor, where he first observed a rudimentary plasma, which twenty years later supplied the inspiration for the fusor.

.

.

Billions -v- Millions

As has been discussed at length all over this site, it is ironic to the point of bemusement that countless billions of dollars have been spent on brute-stgrenth approaches to controlled nuclear fusion – but nary a dime spent to dig deeply into the riddle of the Farnsworth Fusor.

Yeah, yeah, I know the prevailing wisdom: Farnsworth himself was incapacitated the whole time the fusor project was burning through (really, not a whole lot of) ITT’s cash in Fort Wayne; The fusor is just another idle curiosity and will never really amount to anything useful other than as a neutron generator.

And then there is the even more debilitating insistence that useful energy from controlled fusion lives forever beyond the reach of human understanding: it’s twenty years in the future and always will be.

Maybe we’re asking the wrong humans?

I also know what I learned from spending a lot of time with Farnsworth’s family, in parrticualr his eldest son Philo III, and his insistence that his father “rarely went down blind alleys” – and certainly not with a major conception like the fusor.

The bottom line for me is: where the fusor is concerned, there are more questions than there are answers. Chief among them is the question I posed to Robert Hirsch – who cut his teeth as a Fansworth colleague before becomig the DOE’s top fusion bureaucrat and steering mountains of money toward the tokamak in the 1970s and 80s. .

When asked Hirsch why the ITT Fusor project ended so inconclusively, he answered with three damning, inscrutable words:

Not enough money.

And why not? Because the bureaucracy that Hirsch eventually commanded was suspicious of Farnsworth, his background and his methodology. Hirsch also said:

The scandal in the whole thing, and the thing I don’t understand to this date—and maybe never will—is how those people would not open up to the possibility of a Farnsworth-like idea.

I think they were … uncomfortable with Farnsworth… an inventor…with just dribs and drabs of education, who in fact conceived and developed one of the most significant technological advances of the 20th century, and here he was coming along in fusion? I don’t know whether it was ego or what but there is something strange there…

Strange? Ya think?

And then I’ll read yet another press release from yet another company that has raised nearly a billon dollars to build yet another brute-force fusion machine.

So how exactly is that a field as compelling as fusion energy can draw billions for sprawling, complicated monotliths – but nary a dime for something as simple and elegant as the fusor?

Well, it’s time we found out.

Hence The Waterstar Foundation.

Now that we have a 501c3 tax-exempt organization, it’s time we run this sucker up the flagpole and see if we can get anyone to salute.

Paraphrasing (and updating) what I first wrote in The Waterstar Manifesto back in 2019:

Before it was dissolved in 1968, the Farnsworth fusion program cost ITT an annual budget of $400.000. That translates to roughly $4-Million in 2024 dollars.

Under the 501c3 umbrella, I propose to raise $100-million.

Not to spend. To invest in a perpetual endowment.

An annual draw of 4% from an endowment of $100-million will provide $4-million/year – the 2024 equivalent of the money ITT was not willing to spend in 1968.

Given the relatively low cost of building and operating a fusor, that should be sufficient to sustain a meaningful effort to arrive at a definitive conclusion: Either the fusor produces useful fusion energy, or we will conclude without equivocation that the approach is a dead end – at which point the endowment will be dissolved.

This is a win-win proposition with no deadline. Either we find a path toward useful fusion energy (the benefits of which are incalculable) or we reach an incontrovertible dead end and return the princpal funds to their sources or divert them to some other useful purpose. LIke, I dunno, sending Elon Musk to Mars.

I admit I am well out of my depth here. I’ve never raised the kind of money I’m talking about here. The most ‘capital’ I’ve ever raised was the $1,000 two friends and I invested in 1995 to start songs.com (which we sold five years later for several million – not a bad return on the initail investment).

Maybe I am deluding myself thinking this sort thing done happens all the time, that it might be possible to get some oligarchs to care enough about their tax deductions to pitch a few million into a philanthopic effort to solve the world’s climate-and-energy challenges.

I’m not sure where to start, but it can’t hurt to at least try. And as the (draft) mission statement for the Foundation says, there are other elements of this initiative that could draw attention to these initiatives.

Consider this post the first flag planted.

The Metaphysics of It All

After 25 years of working with him in the devlopment of this website, I am intimately familiar with Richard Hull’s curmudgeonly insistence that the fusor will never amount to anything truly useful. At least Richard and I are in complete agreement that all the other efforts to control and utilize fusion energy will likewise come to naught.

And it could be too late to overcome the other consensus – based largely on considerable time Richard spent with the the alumni from Pontiac Street – that Farnsworth was out of his gourd, incapacitated and disengaged in the real work that was going on there.

But I am more inclined to think that he was sandbagging.

I think Farnsworth knew exactly what he was doing (even if the polarity of the first iterations of the fusor may have been inside out). His initial inspiration – drawn form the depth of that well he first dipped into five decades earlier – made him uniquely qualified to see beyond a mere replacement for fossil fuels to a civilization far beyond what we can foretell with our chemical-and-combustion-constrained imaginations. And I am not surprised that he harbored deep reservations about whether mankind is ready to take such a leap.

I think this reticence is reflected in something that Farnsworth himself said that I have been quoting lately in my presentations about my books.

I know that God exists. I know that I have never invented anything. I have been a medium by which these things were given to the culture as fast as the culture could earn them. I give all the credit to God.

Now, I am the last person to put any credence in ancient, anthropomorphic deities. But I do think Farnsworth has expressed here the real reason there are so many questions about the fusor: some things must remain out of reach until the culture has earned them.

Until then, fusion research needs the spirit that Cliff Gardner invoked back in 1930.

When Vladimir Zworykin visited the Farnsworth lab in San Francisco – in order to purloin Farnsworth’s work for his employer back east, David Sarnoff’s RCA – he was shown several techniqutes unique to the Green Street operation . As described in Chapter 7 (A Beautiful Instrument):

One of the features of the Image Dissector that caught Zworykin’s attention was the flat, optical glass sealed into the end of the tube. Marveling at the construction, Zworykin said to Phil and Cliff, “My people told me this couldn’t be done.”

“Well,” Cliff replied, “we didn’t know it couldn’t be done, so we just went ahead and did it.”.

That’s what fusion research needs. Somebody who does’t know what can’t be done so that they are free to just go-the-fuck-ahead and do it.

Which is the ultimate metaphysical logic behind The Waterstar Foundation and the dare-to-dream endowment that I would like to call “The Excalibur Fusion Fund” – as envisioned in this passage from the epilogue the book:

Like the mythological sword Excalibur, the secret of the Fusor lies frozen in the rock of institutional orthodoxy.

A few nuclear physicists around the world are beginning to experiment with the Fusor, but their funding is still inadequate. There is also a dedicated cadre of scientific amateurs who are building their own small Fusors.

So let us build an endowment, to which professional and amateur alike can pitch ideas that would otherwise receive no consideration or funding. And then…

Like the knights and squires of the ancient legend, these would-be kings can stand on the rock and try with all their might to pull the sword from the stone. But when the time is right, the mystery will reveal itself, the stone will unlock its secrets, the quiet passion of Philo T. Farnsworth will be reawakened, and the dawn of a new civilization will be upon us.

It may sound outrageous, but… there are a lot of dumber ideas out there that are getting all the money they ask for.

Honestly, it’s all about the story. And this is a damn good one!

The harder part is getting even a few shekels siphoned off for the unorthodox ideas that are found only on the periphery.

The GoFundMe portal for the Excalibur Fusion Fund is now open .